by Gideon Lazar

The Current Debate

It is well known that the doctrine of creation is under attack. Modern science has been misused to banish belief in creation as described in scripture and textual criticism has been misused to attack the very integrity of scripture itself.

Meanwhile modern theological movements have sought to weaken the authority of the Fathers and Doctors of the Church.

However, there is an even more troubling trend regarding the doctrine of creation than even the veracity of scripture: the free act of creation. One of the key historic Christian doctrines since the earliest days of the Church has always been that God freely chose to create. Edward Feser and David Bradshaw have both done a good job showing this from the Church Fathers.

In contrast to this, many modern theologians, such as John Milbank, Eric Perl, and David Bently Hart, have argued that because God is His nature, God could not have done otherwise than create. Fr. James Dominic Rooney and Edward Feser have done a good job pointing out this error in Hart. I wish to focus in on a specific quote by John Milbank:

God freely wills Creation to be just as much and no more than he freely wills himself to be. (Source)

That is, creation is no more a free act of God than his own existence is. This would mean that either creation is necessary, or God’s own existence is contingent. Both of these would be heretical. In fact, Vatican 1 anathematized Milbank’s statement almost word for word:

If anyone… holds that God did not create by his will free from all necessity, but as necessarily as he necessarily loves himself… let him be anathema. – Vatican 1, Dogmatic Constitution of the Catholic Faith 1.5

Of course, Milbank is an Anglican and so would not worry much about his opinions being anathematized. But Milbank is extremely popular in Catholic theology these days and has been published extensively in Catholic theological journals such as Communio. For example, his error has been almost repeated by a Catholic theologian highly influenced by Milbank, D.C. Schindler:

What occurred in the late medieval intellectual movement known as nominalism was a radical shift in perspective: the potentia absoluta was conceived, no longer as an abstraction that exists only in speculation rather than in existence, but as the actual reality of God, his innermost essence, which implies an essential contingency in the God who creates the world and reveals himself in history. He has in fact revealed himself in this particular way, namely, supremely in the incarnation of Christ, but he could have revealed himself in an infinite number of ways, or even not at all. This amounts to saying that the actual revelation we have received is not decisive; it does not in fact disclose anything essential about God. [emphasis added] (Source)

That is, one should not say that God could have created a different way or not at all. Schindler is wrong that this shift was a nominalist one, as it already existed in St. Anselm and St. Thomas Aquinas, two doctors of the Church who were both not nominalists, as Schindler himself notes in the article. Now I do not say this as a personal attack on Schindler (I have many mutual friends with him and have heard nothing but wonderful things about his personal character) or to say he has fallen into the actual heresy that Milbank explicitly has (I would like to hear further clarification as it sounds heretical) but as a genuine concern about the direction of Catholic creation theology away from the solid foundation laid by the Fathers, the Doctors, and the First Vatican Council.

While it is easy to say that those who deny divine freedom to create are wrong, it is harder to explain precisely why they are wrong. Let us then turn to two of the greatest metaphysicians and theologians of Catholic history, St. Thomas Aquinas and Blessed John Duns Scotus, to see how they respond to this error.

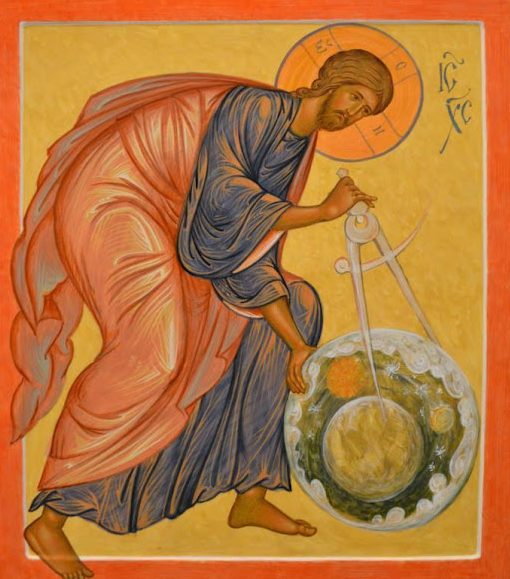

St. Thomas Aquinas on Divine Freedom

In Summa Theologiae 1.25.5, St. Thomas asks whether God can do what he does not do. That is, could God have willed differently than He actually did. St. Thomas answers that God can act either necessarily from His nature or freely from His will. That which is caused from natural necessity is by His absolute power, that is, what He is able to do. However, what God actually causes in the created order is by His ordained power. God is not obligated by His nature to will anything outside of Himself because of this distinction.

Thus, although He possesses an absolute power, God only orders that power in a certain way to the actual creation. This is why St. Thomas in the same article says that there is an “order placed in creation by divine wisdom” but that the divine wisdom is not “restricted to this present order of things.” To put it in other words, there is a certain structure within creation, but God could have chosen a different structure.

This is the key point. God could have chosen a different structure. He is entirely free to choose a different order, and so in some sense there is no cause for creation besides God’s free choice. However, once God does will a particular creation, this creation must be well ordered because of God’s perfect wisdom. This is why Schindler’s claim that the distinction would destroy the revelation of God through creation is false. God does not make an arbitrary creation, but one well ordered to a chosen end.

To understand this better, let’s consider the following analogy. Imagine I wanted to bake a dessert. I could bake a cake or a pie. Cake or pie isn’t necessarily better and it’s up to my choice of which I would like to have. However, once I choose to bake a cake, I have to follow a recipe to make that cake well. If I chose to fill the cake with apples, it would not turn out well. Apples are a perfectly fitting filling for pie, but not for cake. However, there are certain steps that could be done differently. For example, I would choose what color frosting to make for the cake. So the initial choice of the end is totally free, the steps then willed to achieve that end must be fitting to the end.

Of course in the case of humans, we are flawed and so may will out of order. But God always wills in the most orderly way because He is perfect. Likewise, God is infinite and simple, whereas we are finite and composed. This makes it difficult for us to understand the divine will. Let us now turn to the Subtle Doctor, Bl. Scotus, to better understand the divine will.

Bl. John Duns Scotus on Divine Freedom

Blessed John Duns Scotus helpfully builds upon and clarifies the distinction between absolute and ordained power in question 16 of his Quodlibetal Questions. Here he asks whether natural necessity and free will are incompatible. Following the tradition of St. Augustine, St. Maximus, and St. Thomas, Scotus is distinguishing between natural and voluntary powers. Scotus answers that these powers are not always incompatible. For example, God freely loves Himself and by this love spirates the Holy Spirit, but it is not as though God could not love Himself. At first it could sound like Scotus is agreeing with the deniers of divine freedom, but it is here he pivots on a key point. God is loving an infinite end in loving Himself. This infinite end is sufficient to satisfy His natural desire for the good.

God can also will to create and love other things though, and this act of His will is not constrained by natural necessity since the ends are finite. While God does not act contrary to His nature in creating the world, neither is it required by His nature. This also does not mean that the world does not reveal God’s nature. In this same passage, Scotus says that every created thing participates in and reflects God’s goodness. It is only that this particular expression of the world is not required by His nature.

One brief note to consider is that God does not choose in the same way we do. We have to spend time deliberating over options and choosing between them. At a later point, we may change our mind from what we chose. However, God is outside of time and simple. His intellect presents all infinitely possible creations and His will freely chooses one, but as a single eternal act. He does not have to weigh the various options and choose one because He knows them all perfectly by His infinite wisdom, and He will not change His mind in the future because He is unchanging. Scotus therefore concedes a certain kind of necessity to creation, but only in the sense that God will not change His mind and cease to will this world. It is not a necessity of the inability of God to choose otherwise.

Scotus on the Reason for Creation

What then is the end that God wills for the creation He has made? This is where Bl. John Duns Scotus gave his most important contribution to theology. As we saw above, God wills first the end and then the means, and so if we want to understand why God created the world, we must understand the first intention of His will. Scotus points out that lesser things are always done for the sake of greater things. This means that everything must be for the sake of the greatest thing. (Of course the greatest possible thing is God Himself, but Scotus here is thinking in terms of what God does create.)

What is God’s greatest creation? Scotus answers that it is the humanity of Christ, since it is united with His divinity. Therefore, God created everything for the sake of the incarnation! As St. Paul says, “For from him and through him and for him are all things” (Rom 11:36). This teaching of Scotus has come to be known as the Absolute Primacy of Christ, for it places Christ Himself at the forefront of all things that God does. The creation of mankind, the angels, and the whole universe is done in accord with what is fitting with the purpose of the universe, the incarnation. While Scotus’s opinion here is not dogma, it is widely accepted by theologians as the most probable view.

Conclusion

Despite the arguments of certain modern academics, the doctrine that God could have done otherwise in creating is founded upon solid metaphysical ground. It does not divide creation from God, because as we have seen, God still creates for a particular end, the Son, and not in an arbitrary fashion. Likewise, divine freedom with respect to creation was taught by the Fathers and was dogmatized at Vatican 1. There is no reason therefore to abandon this teaching.

Let us use this as an opportunity to meditate upon the goodness of God, who freely chose to create us without any internal necessity of His nature.

One thought on “Creation and Divine Freedom”