by David Valerio

I. Introduction

My book, sir philosopher, is the nature of created things, and it is always at hand when I wish to read the words of God. (Evagrius, para. Praktikos 92)

Stereotypically, the monastic life is perceived as entailing a rejection of the world. In this view, the select men and women who left society in order to enter the wilderness did so in order to save their own souls, unencumbered by temptations from interactions with other created beings. While there is some truth to this, it doesn’t imply that the Desert Monastics detested Creation. In fact, the spirituality of the desert was marked by a profound reverence for Earth. It was embodied, practical, and deeply concerned with the monk’s harmonious relationship with the natural world. To partake in the divine nature and enter into union with God, the monk had to commune with the created world that God made and sustains. How can one love the Creator without loving His Creation, which He saw and called “very good” (Douay-Rheims Bible, v. Genesis 1:31)?

Numerous stories from these spiritual trailblazers attest to their deep connection to and love for the desert they called home. These accounts describe various interactions between monks and the natural world, reflecting how their chosen environment, with its unique environmental conditions, shaped the way that desert spirituality evolved and came to be practiced. This paper proposes to catalog key ecospiritual learnings from Desert Monastic theory and practice by meditating on sayings from the Fathers and Mothers that explore the ascetical-mystical significance of three classical elements — earth, water, and fire. We have much to learn from these ancient Christians who inhabited the wildest of places, and their example can serve as a model for us moderns to come closer to God and live in greater harmony with the world we are intertwined with.

II. Earth

II.I Work and Reeds

The Desert Monastics placed a high value on physical work as a means of drawing closer to God. If the ascetic did not work, his nous would stray from contemplation of God and fall prey to demonic temptations. Engaging in simple manual labor occupied the body, calmed the mind, and provided the monk with a humble means of sustenance. The goal of such manual labor was not the physical fruit that it bore, but rather the inner stillness it fostered. A quintessential example is found at the beginning of the Alphabetical Collection of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers where St. Anthony asked God what he needed to do in order to be saved. God gave him a vision of “a man like himself sitting at his work, getting up from his work to pray, then sitting down and plaiting a rope, then getting up again to pray”. An angel then told him that if he did this, then he would be saved (Ward, para. Anthony the Great 1). The rhythm of prayer and work repeated in perpetuity was the foundation of salvation to the earliest Christian monastics. Indeed, work was so integral to the spiritual life that to be deprived of it was considered to be a loss:

There was a blind elder at Skete in the lavra of Abba Sisoes; his cell was located about half a mile from the well. He would never allow anyone else to fetch water for him. He made a rope and attached one end of it to the well, the other to his cell; the rope lay on the ground. When he went to fetch water, he walked along the rope. The elder did this so that he could find the well that way. When the wind blew the sand so that it covered the rope, he would take it up in his hand, shake it and put it back down on the ground and walk along it. When a brother offered to fetch water for him, the elder replied: ‘Truly brother, for twenty-two years I have fetched my own water; so you wish to deprive me of my labour?’ (Moschos, chap. 169)

What would have been perceived as a generous act by a layman was seen as a slight by the monk. Work was a non-negotiable aspect of monastic life. If one did not work, neither would one eat, either physically or spiritually (v. 2 Thessalonians 3:10).

A recurring theme throughout the early monastic literature is the confrontation between orthodox Christianity and the Euchite, or Messalian, heresy (“Messalians”). The Euchites rejected the spiritual importance of the sacraments, despised physical disciplines, and believed that prayer alone was necessary for salvation. The Desert Monastics rejected this disembodied philosophy as being utterly antithetical to Christian spirituality. A prime example of this is the story of Abba Lucius’ encounter with a band of Euchites. When he asked them what their manual work was, they responded that they had none. Rather, they preferred to “pray without ceasing”. Abba Lucius then proceeded to ask them who prayed for them while they were sleeping and received no response. He then said:

Forgive me, but you do not act as you speak. I will show you how, while doing my manual work, I pray without interruption. I sit down with God, soaking my reeds and plaiting my ropes, and I say, ‘God, have mercy on me; according to your great goodness and according to the multitude of your mercies, save me from my sins.’ (Ward, para. Lucius 1)

With the money obtained by this work, he was able to pay others to pray on his behalf while he was sleeping and thus fulfill the commandment. This story shows how ridiculous the denial of material creation as evil was to the orthodox Christian ascetic. Naïve spiritualism had no place in the desert. The human person is a body-soul composite and must strive for salvation in a manner that reflects this reality.

What valuable work could be conducted without the raw materials necessary to fashion cloth, rope, or baskets from? The most important natural resource the monks used to produce these goods were the papyrus sedges, common reeds, aquatic bulrushes, and sea rushes that grew along the riverine distributaries and terrestrial wetlands of the Nile Delta (“Nile Delta Flooded Savanna”; Rebelo and McCartney 220). The role of aquatic vegetation in the monastic way of life is shown by the story of “a great elder [that] came to the river and, finding a placid reed bed, settled there”. From this home base, he cut shoots from the reed bed and braided them into ropes, which he then proceeded to throw into the river. We are told that “he did not work because he needed to but for the toil and for hesychia” (Wortley 22). This account is ambivalent with respect to the loving stewardship of nature, as the way he negligently disposed of his work products in the river shows how the desert Christian could negatively impact the natural world around him through his pursuit of holiness (Wheeler 183). Nonetheless, it emphasizes that without the natural capital found in his surrounding environment, the monk could not conduct his work for God.

II.II Love and Geography

The physical environment that the monks chose to make their homes in had a deep spiritual impact on their practice of the Christian faith. There is a reason that they are known to history as the Desert Monastics, since their encounter with the barren landscapes of the arid Near East was reflected in their equally lean, harsh spirituality (Lane 1). The grand vistas to be seen in these “wastelands” lifted the monk’s mind and heart up to meditate on the transcendent mysteries of our ineffable, invisible, incomprehensible God. The isolation found in these places unfit for civilization allowed the monk to commune in an intimate way with our Lord, God, and Savior Jesus Christ, without the distractions of the human world to entice them away from the mystical path of theosis. The biosphere even warned the monks about spiritual dangers that might arise and how to escape them: “When you see a cell built close to the marsh, know that the devastation of Scetis is near; when you see trees, know that it is at the doors; and when you see young children, take up your sheep-skins, and go away.” (Ward, para. Macarius the Great 5)

A common trope about early Christian monasticism is that it reflects a Gnostic hatred for the created world. This is far from the case. We are told that when St. Anthony first approached his Inner Mountain:

He came to a very lofty mountain, and at the foot of the mountain ran a clear spring, whose waters were sweet and very cold; outside there was a plain and a few uncared-for palm trees. Antony then, as it were, moved by God, loved the place, for this was the spot which he who had spoken with him by the banks of the river had pointed out. (St. Athanasius, para. 49)

Far from despising the place that he had been called to live in, he saw the beauty of the mountain, with its flowing waters and isolated palms, and instantly fell in love with it. Love is the key word here. The Lord reminds us that the first and greatest commandment is to “love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with thy whole mind”, and that the second, “thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself”, is intimately bound up with the first (v. Matthew 22:37-39). What does it mean to love a place? We have a good idea of what love in action looks like when the object is a human person. Sacred Scripture and Holy Tradition contain innumerable examples of how the love of man for his fellow man is an icon of the inner life of the Holy Trinity, who is love incarnate and in essence. Love for one’s ecosystem is less clear but nonetheless can be explored through the use of analogy. The fact that after St. Anthony made his home there, he “found a small plot of suitable ground, tilled it; and having a plentiful supply of water for watering” sowed it indicates that love for Creation entails working it into something more fecund than it is by nature alone (St. Athanasius, para. 50). Abba John the Eunuch lets us know what love for a place does not look like when he tells his disciples, “My sons, let us not make this place dirty, since our Fathers cleansed it from the demons.” (Ward, para. John the Eunuch 5) Love for the environment was central to Desert Monastic spirituality, but the way it was expressed was specific to particular geographies, analogous to how their sayings on human relationships are specific to the particular people involved.

III. Water

III.I Thirst and Trust in God

The deserts of Egypt, Syria, Palestine, and Cappadocia are very dry places. The Nitrian Desert of Egypt, a subregion of the larger Western Desert where the early monastic centers of Scetis, Kellia, and Nitria were located, receives on average less than two tenths of an inch of precipitation annually and can go half-centuries or more without receiving any rainfall whatsoever (Williams 1). Water is necessary for life. The typical human being can go seven days without drinking water, but in the extreme environments of the earliest monastics this could be as short as seven hours due to the sweltering conditions they encountered and the strenuous walking they often undertook (Piantadosi 52–53). With this context, one is better equipped to understand just how perilous a situation St. Macarius the Great found himself in when “the water he was carrying [during a twenty-day journey] was exhausted” and was thus in great distress. He was at the point of collapse when a maiden appeared to him “holding a dripping bottle of water and standing about a furlong away from him”. This was a mirage that he pursued for three days, and “after her a herd of buffalo appeared to him; a female with a young one came to a halt. Her udder was flowing with milk. He got beneath her and was relieved by sucking her. The buffalo came as far as his cell, suckling him while not letting her calf near her.” (Palladius, para. Macarius of Alexandria 8-9) This story underscores how God will provide drink to those who thirst for Him, sometimes through the intercession of His creatures (v. Psalm 62:2-3). This was also the case when St. Sabas prayed to God for the relief of a little water in the early days after the foundation of the Great Lavra, subsequently seeing “a wild ass digging deep into the earth with its hooves; when it had dug a large hole, he saw it lowering its mouth to the hole and drinking”. He was then able to find an unceasing source of flowing water for his monks to drink from going forward (Cyril of Scythopolis, para. Life of Sabas 17).

These accounts of God providing for his servants’ thirst foreground the weighty spiritual reality that “not in bread alone doth man live, but in every word that proceedeth from the mouth of God (v. Matthew 4:4). We can do nothing without the Lord. When we try to rely on ourselves, we deny God’s omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence:

Abba Doulas, the disciple of Abba Bessarion said, ‘One day when we were walking beside the sea I was thirsty and I said to Abba Bessarion, “Father, I am very thirsty.” He said a prayer and said to me, “Drink some of the sea water.” The water proved sweet when I drank some. I even poured some into a leather bottle for fear of being thirsty later on. Seeing this, the old man asked me why I was taking some. I said to him, ‘Forgive me, it is for fear of being thirsty later on.’ Then the old man said, ‘God is here, God is everywhere.’ (Ward, para. Bessarion 1)

Living in a brutal, alien environment had a way of shocking the monks out of their remnant belief in the myth of self-sufficiency. How could he foolishly choose to rely on himself when he saw how quickly he would perish without the Lord to preserve him? This does not mean that the monk could just freeload off God’s grace to survive in the desert. He had to constantly beseech the Lord’s great mercy in order to endure. One time Abba Moses was planning to make a long trip and wondered how he would be able to find the water he needed to get there. A voice told him, “Go, and do not be anxious about anything.” He ended up using his small bottle of water to cook food for some visiting monks, so he argued with God, saying, “You brought me here and now I have no water for your servants”, until God sent them some water (Ward, para. Moses 13). The monk must pray with all his heart, mind, and soul lest he not be heard by the Lord. One time some monks who came to Abba Xoius complained about their distress due to a lack of rain. He recommended that they pray. They replied that they said litanies and still it did not rain. Abba Xoius told them that the reason it did not rain is because they did not pray with intensity, and asked if they wanted to see whether he was right. To show them, he “stretched his hands towards heaven in prayer and immediately it rained” (Ward, para. Xoius 2). One must “ask, and it shall be given you: seek, and you shall find: knock, and it shall be opened to you” with faith, hope, and charity. “For every one that asketh, receiveth: and he that seeketh, findeth: and to him that knocketh, it shall be opened.” (v. Matthew 7:7-8)

III.II Erosion and Spiritual Growth

Water works slowly. Many of the most beautiful vistas we find on our planet — the glorious ravines of Zion National Park, the brilliant badlands of North and South Dakota, the magnificent Mississippi River birdfoot delta — were shaped by weathering and erosion, geologic processes set in motion by that most elegant of molecules, H2O. (“Geology – Zion National Park”; “Geologic Formations”; “How Was the Mississippi River Delta Formed?”). Yet, water is so widespread as to be ignored (in many places at least). How could such an everyday liquid be so necessary to the existence of life itself, as well as pivotal in shaping the very face of the Earth? The Desert Monastics pointed to the patient, long-suffering work of water as a symbol of how the monk should be while progressing in spiritual life. This can be seen in this story about Abba John the Dwarf:

It was said of Abba John the Dwarf that he withdrew and lived in the desert at Scetis with an old man of Thebes. His abba, taking a piece of dry wood, planted it and said to him, ‘Water it every day with a bottle of water, until it bears fruit.’ Now the water was so far away that he had to leave in the evening and return the following morning. At the end of three years the wood came to life and bore fruit. Then the old man took some of the fruit and carried it to the church saying to the brethren, ‘Take and eat the fruit of obedience.’ (Ward, para. John the Dwarf 1)

One cannot expect to achieve Christian perfection in a matter of days, months, or years. Final flourishing in the life in Christ is a process that unfolds over the course of one’s whole life, on the timescale of decades. We must continue to water our spirit with the practices of prayer, fasting, and almsgiving so that the Lord will grant us the grace to grow as the mustard seed, “which is the least indeed of all seeds; but when it is grown up, it is greater than all herbs, and becometh a tree, so that the birds of the air come, and dwell in the branches thereof” (v. Matthew 13:31).

Water drips. We see this happen often at our kitchen faucets, when they have a worn-out washer or a loose o-ring. It’s annoying when this occurs. Yet, these slow dribbles can also produce marvels. One need only see the stalagmites and stalactites of the Carlsbad Caverns of New Mexico to grasp the wonder-working power of slow splashes of water over long periods of time (“Geology Of Carlsbad Caverns National Park”). Abba Moses once used this hydrologic process to point out the hypocrisy of his fellow monks, in the understated way characteristic of the Desert Monastics:

A brother at Scetis committed a fault. A council was called to which Abba Moses was invited, but he refused to go to it. Then the priest sent someone to say to him, ‘Come, for everyone is waiting for you.’ So he got up and went. He took a leaking jug, filled it with water and carried it with him. The others came out to meet him and said to him, ‘What is this, Father?’ The old man said to them, ‘My sins run out behind me, and I do not see them, and today I am coming to judge the errors of another.’ When they heard that they said no more to the brother but forgave him. (Ward, para. Moses 2)

The protracted, inconspicuous loss of water from the jug emphasizes how cunning the Devil can be when dragging us down from the spiritual heights we are called to. How easy it is to “seest the mote that is in [our] brother’s eye; and seest not the beam that is in [our] own eye” (v. Matthew 7:3)! The small sins that we fail to notice build up over time, and eventually lead to dramatic spiritual falls.

Abba Poemen once said that “the nature of water is soft, that of stone is hard; but if a bottle is hung above the stone, allowing the water to fall drop by drop, it wears away the stone. So it is with the word of God; it is soft and our heart is hard, but the man who hears the word of God often, opens his heart to the fear of God.” (Ward, para. Poemen 183) These beautiful lines call attention to the necessity of consistency in spiritual life. To constantly have the Word of God in our mind, on our lips, and in our heart is to always have God before our eyes, as St. Anthony enjoins us to do (Ward, para. Anthony the Great 3). In doing this, we allow the Lord to excise our evil habits and leave Jesus Christ to iconographically shine through in the way we live. Lao Tzu, the semi-legendary ancient Chinese philosopher and composer of the Tao Te Ching, notes this perennial truth about the portentous potentialities of water when he states: “Nothing in the world is as soft, as weak, as water; nothing else can wear away the hard, the strong, and remain unaltered. Soft overcomes hard, weak overcomes strong. Everybody knows it, nobody uses the knowledge.” (Lao Tzu, chap. 78 Paradoxes) The dichotomies, paradoxes, and inversions emblematic of Taoism are also core to Eastern Christianity (Hieromonk Damascene). St. Paul tells us that when we are weak, then we are powerful (v. 2 Corinthians 12:10). The Lord tells us that “whosoever shall exalt himself shall be humbled: and he that shall humble himself shall be exalted” (v. Matthew 12:12). The Desert Monastics willingly flowed to the lowest place in their social landscape. They were content to live in caves and holes in the ground, to subsist off bread and foraged vegetation, to pray and work the most mundane tasks. They made fools of themselves for Christ’s sake, and in so doing received their crowns of righteousness (v. 1 Corinthians 4:10, 2 Timothy 4:8).

IV. Fire

IV.I All Flame

God appeared to Moses as a fire writhing within an incombustible burning bush (v. Exodus 3:22). The Holy Spirit descended upon each of the Apostles at Pentecost as tongues of fire (v. Acts 2:3). St. Paul says that our God is a consuming fire (v. Hebrews 12:29). Abba Joseph once said, “You cannot be a monk unless you become like a consuming fire.” (Ward, para. Joseph of Panephysis 6). For the monk to become all flame was for him to become like God. Fire is not a static object, it is a dynamic process. Fire is never the same. It constantly expands and contracts as it interacts with the biogeochemistry of the surrounding environment. It transforms solid matter into ephemeral gas. In a sense, it relates to the outside world in a similar way to how the three persons of the Holy Trinity relate to one another. Fire is a communion of elements. The idea of the monk being like fire is related to Abba Bessarion’s statement: “The monk ought to be as the Cherubim and the Seraphim: all eye.” (Ward, v. Bessarion 11) The monk must constantly be vigilant; he need always be on watch. He must unceasingly commune with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The following image of the venerable Abba Arsenius, one of the most widely respected of the early Egyptian ascetics, shows us how fire was an icon of the true Desert Monastic:

A brother came to the cell of Abba Arsenius at Scetis. Waiting outside the door he saw the old man entirely like a flame. (The brother was worthy of this sight.) When he knocked, the old man came out and saw the brother marvelling. He said to him, ‘Have you been knocking long? Did you see anything here?’ The other answered, ‘No.’ So then he talked with him and sent him away. (Ward, para. Arsenius 27)

We also have this remarkable saying from Abba Joseph to ponder as we consider the significance of fire to the spiritual life of the desert:

Abba Lot went to see Abba Joseph and said to him, ‘Abba, as far as I can I say my little office, I fast a little, I pray and meditate, I live in peace and as far as I can, I purify my thoughts. What else can I do?’ Then the old man stood up and stretched his hands towards heaven. His fingers became like ten lamps of fire and he said to him, ‘If you will, you can become all flame.’ (Ward, v. Joseph of Panephysis 7)

The monk was to conform himself to God in the present moment, at all times, and in all places. He was not to think about the past or future, but rather live out the commandments in the here and now by dying to self. Fire does not self-reflect. It simply acts. It simply is. The logismoi cannot touch the monk who is on fire with the Lord, since the demons cannot take him away from the ever-present now. To become all flame is to be fully before the face of God and to be transfigured by Him. Ultimately, fire is a mystery as the Trinity is mysterious. We can explain how it emerges, grows, and persists in as many ways as we like, applying both cataphatic and apophatic knowledge, but the conclusion of our reasoning will lead us back to where we started. What does it mean to be all flame? Who knows. Only God does.

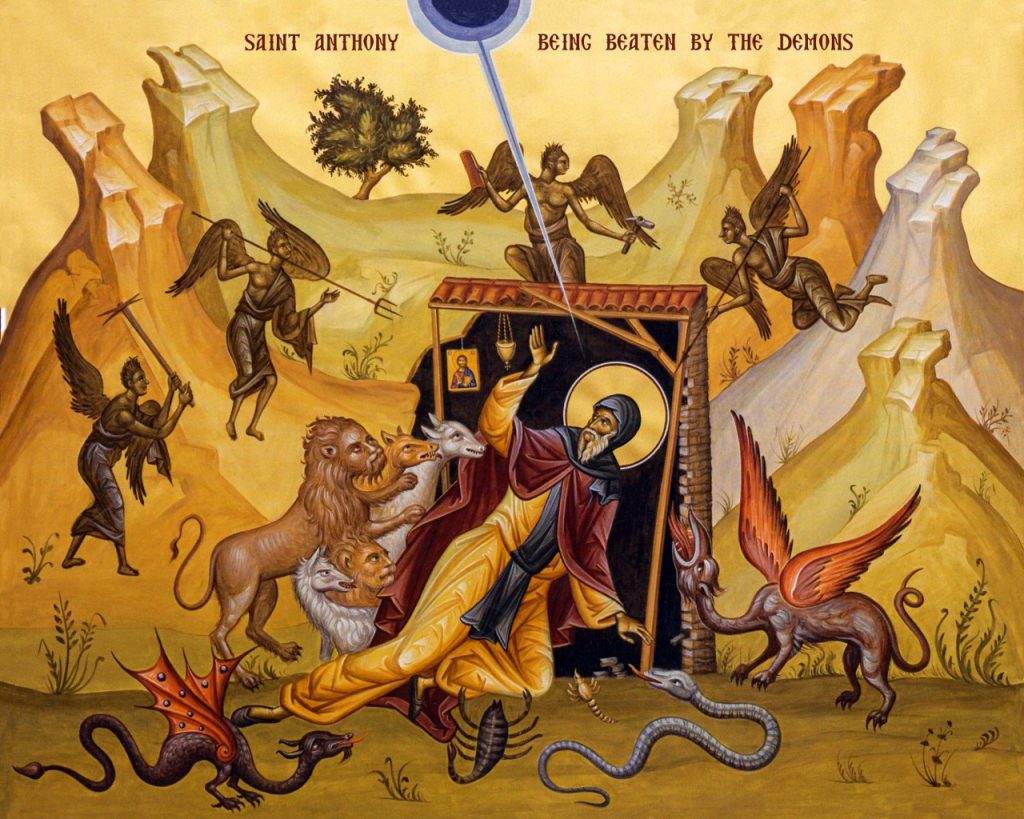

IV.II Refining Fire and Uncreated Light

Being cleansed of our sins is hard. We would like to be good, but as St. Paul says: “For the good which I will, I do not; but the evil which I will not, that I do. Now if I do that which I will not, it is no more I that do it, but sin that dwelleth in me.” (v. Romans 7:19-20) The demons must be cleared out of us. The Desert Monastics knew this very well from their eternal battles with them in the heart of the desert. Yet this process of purification is often painful. The Lord refines us as fire burns away the imperfections of silver and gold (v. Proverbs 17:3). To be thrown into the blazing flames and have our vices incinerated involves many trials and much suffering, but ultimately we come out the better for it. Amma Syncletica spoke to this fact when she said:

In the beginning there are a great many battles and a good deal of suffering for those who are advancing towards God and afterwards, ineffable joy. It is like those who wish to light a fire; at first they are choked by the smoke and cry, and by this means obtain what they seek (as it is said: “Our God is a consuming fire”): so we also must kindle the divine fire in ourselves through tears and hard work. (Ward, para. Syncletica 1)

If we make it through the smoke first kicked up in our attempts to kindle the divine fire of the Holy Spirit within us, we will soon nurture an overpowering internal inferno that scorches our sins so quickly that the fumes do not even have time to rise. We must become so burning hot through embodying heroic virtue that our enemies cannot get anywhere near us. As soon as evil thoughts come into our minds, we must dash them against Christ (St. Benedict, v. 3:50). Abba Poemen once said, “As long as the pot is on the fire, no fly nor any other animal can get near it, but as soon as it is cold, these creatures get inside. So it is for the monk; as long as he lives in spiritual activities, the enemy cannot find a means of overthrowing him.” (Ward, para. Poemen 111) If we spend our lives in peace and repentance, the Lord will be there to redeem and save us. We must simply continue to stoke our hidden fire with the fuel of passionate prayer.

Fire and light are inextricably linked. Before the electric age, the only sources of light to brighten the night throughout all of human history employed fire — torches, candles, oil lamps. Light was a scarce, precious resource. It was something to be treasured for its battles against darkness. To have a source of light with you was a matter of life or death. Thus, the weight of Christ saying that he is “the light of the world: he that followeth [him], walketh not in darkness, but shall have the light of life” (v. John 8:12). He who has the Lord by his side should have no fear in the face of the “principalities and powers, [the] rulers of the world of this darkness, the spirits of wickedness in the high places” (v. Ephesians 6:12). Jesus tells us that we, too, are meant to be the light of the world, and that we should shine like the sun with our clothes white as snow (v. Matthew 5:42, 17:2). One time, “Abba Hilarion went to the mountain to Abba Anthony. Abba Anthony said to him, ‘You are welcome, torch which awakens the day.’ Abba Hilarion said, ‘Peace to you, pillar of light, giving light to the world.’” (Ward, para. Hilarion 1) This interaction between Abba Hilarion and Abba Anthony demonstrates the close connection between external light and internal holiness. St. Seraphim of Sarov, a Russian hermit of the 19th century who emerged out of the ascetic tradition of the Northern Thebaid, once startled his disciple with the physical manifestations of his transfiguration in the Holy Spirit (Rose):

Then Father Seraphim took me very firmly by the shoulders and said: ‘We are both in the Spirit of God now, my son. Why don’t you look at me?’ I replied: ‘I cannot look, Father, because your eyes are flashing like lightning. Your face has become brighter than the sun, and my eyes ache with pain.’ Father Seraphim said: ‘Don’t be alarmed, your Godliness! Now you yourself have become as bright as I am. You are now in the fullness of the Spirit of God yourself; otherwise you would not be able to see me as I am.’ (Zander)

The holiest monks reflected the uncreated light of the Holy Trinity in their every word, deed, and thought. In doing so, they became superior, living icons of Christ, and warmed the world around them with the gift of their presence. The ultimate calling of every Christian, not just those who are monks, is to be transformed into God’s likeness by putting on the new, true man — Jesus Christ, the New Adam (v. Ephesians 4:24, 1 Corinthians 15:45). The earliest Christian ascetics show us the way to achieve Christian perfection, and give us the spiritual tools necessary to enter into union with God.

V. Conclusion

This journey into the spiritual landscape of the Desert Monastics reveals the sublime interrelations between the elemental forces of earth, water, and fire, and the quest for union with God in the lives of the earliest desert dwellers. These first Christian ascetics, through their austere and contemplative existence, exhibited a symbiotic relationship with these elements, each serving as a conduit to deeper spiritual truths. Earth, encountered in their rigorous manual labor and the simplicity of their monastic environment, emerged as a teacher of humility and self-discipline. Through tasks as prosaic as the plaiting of reeds, the monks engaged in a form of living prayer, where physical work became a medium for stillness. Water, scarce yet life-sustaining, surfaces as a symbol of God’s unremitting providence and a metaphor for spiritual thirst. The monks’ experiences of divine support in dire times of need serve as remarkable parables of God’s nurturing presence that emphasize the necessity of constant reliance on the Lord while striving for holiness. The slow, transformative power of water to shape landscapes over time mirrors the gradual process of increasing spiritual perfection, where persistence and faith carve out the path of sanctification. Fire, through its dynamic and metamorphic nature, encapsulates the fervor and intensity of the monastic pursuit of God. In its flames, the monks saw a reflection of the Holy Spirit’s work within them, purifying and refining their souls damaged by sin. The dual functions of fire — both as a force for inner transformation and a source of illuminating, uncreated light — captures the monk’s role as both a recipient and bearer of the gift of God’s transfiguring grace.

The Desert Monastics’ profound reverence for nature challenges contemporary Christians to re-envision our relationship with the biosphere. Their lives invite us to view the natural world not as a mere resource to be exploited, but as a sacred space that mirrors and facilitates our deeper contemplative union with God. Their examples urge us to seek harmony with Creation as we pursue Christian perfection. The intense connection the monks had with earth, water, and fire offers us a compelling, holistic model for embodied spiritual practice and an intuitive, orthodox understanding of our place within the grand tapestry of God’s magnificent Creation.

Bibliography

Cyril of Scythopolis. The Lives of the Monks of Palestine. Cistercian Publications, 1991.

Douay-Rheims Bible. Saint Benedict Press, 2000.

Evagrius. The Praktikos & Chapters on Prayer. Cistercian Publications, 1972.

“Geologic Formations – How Badlands Buttes Came to Be.” U.S. National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/badl-geologic-formations.htm.

“Geology – Zion National Park.” U.S. National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/zion/learn/nature/geology.htm.

“Geology Of Carlsbad Caverns National Park.” U.S. Geological Survey, https://www.usgs.gov/index.php/geology-and-ecology-of-national-parks/geology-carlsbad-caverns-national-park.

Hieromonk Damascene. Christ the Eternal Tao. Valaam Books, 1999.

“How Was the Mississippi River Delta Formed?” Loyola University Center for Environmental Communication, https://lucec.loyno.edu/how-was-mississippi-river-delta-formed.

Lane, Belden C. “Desert Catechesis: The Landscape and Theology of Early Christian Monasticism.” Anglican Theological Review, vol. 75, no. 3, 1993, pp. 292–314.

Lao Tzu. Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching: A Book about the Way and the Power of the Way. Translated by Ursula K. Le Guin, Shambhala, 1998.

“Messalians.” Catholic Encyclopedia, https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10212a.htm.

Moschos, John. The Spiritual Meadow. Gorgias Press, 2010.

“Nile Delta Flooded Savanna.” Wikipedia, 6 July 2023. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Nile_Delta_flooded_savanna&oldid=1163710940.

Palladius. The Lausiac History. Cistercian Publications, 2015.

Piantadosi, Claude A. “Water and Salt.” The Biology of Human Survival: Life and Death in Extreme Environments, edited by Claude A Piantadosi, Oxford University Press, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195165012.003.0005.

Rebelo, Lisa-Maria, and Matthew P. McCartney. Wetlands of the Nile Basin. International Water Management Institute.

Rose, Fr. Seraphim. The Northern Thebaid: Monastic Saints of the Russian North. St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2004.

St. Athanasius. “Life of Antony.” The Complete Ante-Nicene & Nicene and Post-Nicene Church Fathers Collection, edited by Philip Schaff, Catholic Way Publishing, 2014.

St. Benedict. The Rule of St. Benedict. Liturgical Press, 1981.

Ward, Benedicta. The Sayings of the Desert Fathers: The Alphabetical Collection. Mowbray, 1981.

Wheeler, Rachel. “The Revelatory Tide: Desert Spirituality and Contemporary Water Crises.” Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality, vol. 20, no. 2, 2020, pp. 176–93, https://doi.org/10.1353/scs.2020.0030.

Williams, Martin, editor. “West of the Nile: The Western Desert of Egypt and the Eastern Sahara – Part 1.” The Nile Basin: Quaternary Geology, Geomorphology and Prehistoric Environments, Cambridge University Press, 2019, pp. 211–26. Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316831885.016.

Wortley, John, editor. The Book of the Elders: Sayings of the Desert Fathers; The Systematic Collection. Liturgical Press, 2012.

Zander, Valentine. St. Seraphim of Sarov. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1975.