by Vito Čapeta

The human person is a dynamic being: retaining the past, open to the future. They have experiences and encounters that transform them. They cannot predict how experiences will affect them. The person is a mystery: neither the person themselves nor others can fully know them from the outside. The person cannot be studied as a “how,” but as a “who” and the more we know them, the more complex they are. The person possesses a more proper act of being that makes them more perfect = agere sequitur esse. We act for ourselves and this is an expression of our individuality. Being human is intrinsically and constitutively relational. In order to fully realize ourselves, we have this horizontal openness towards other people to flourish as individuals. Therefore, we are social beings capable of establishing relationships. We are social beings: we exist in society. We have a cognitive orientation towards reality, towards everything that surrounds us. We have relationality because from the womb, we have good and bad experiences, some of which we can overcome, perhaps not always all of them. Children are open to cognitive reality: they touch, experiment, ask…we have the autonomy of action: I self-determine through the reason-will binomial. Relationality is the consequence of the metaphysical structure of reality – the relationship with God as creator, also with parents (reciprocal relationship) is at the origin of the person. It is not conceivable for a person to exist without relationships. In fullness, the person is only given in God who is Trinity. There is a paradox: Man is an independent individual with his own clothes, glances – nonetheless, relational in terms of interpretation, language, nourishment, medical, psychological and spiritual problem-solving. Here we are as human beings, a totality of body-mind and spirit and as such, we are also vulnerable on these levels, such as psychological or psychiatric. For this reason, as “we do not fully know ourselves through simple introspection,” and we are not “able to save ourselves,” we need others to help us. One form of psychological help consists precisely in the relationship between the psychotherapist and the suffering patient. It must be understood that the person is capable of exceeding themselves and being more than what they are. The self is not realized at any point in life – it is not “I am this and that, and that’s it!”

The ideal of the psychoanalyst’s vocation is to help others.

There are suggestions from Allen Frances who proposes the principles that should guide the clinical interview for diagnosis. Now, the focus is on the relationship. (Of course, because we are constitutionally made that way). Diagnosis is a joint effort. Above all, in the initial phases of the psychotherapist-patient interaction, one must adopt a balanced position without immediately jumping to diagnostic conclusions. One must maintain a proper balance between open-ended questions and checklist questions. Additionally, it is good to ask screening questions and aim for a diagnosis. It is important to keep in mind that symptoms must have clinical significance and evaluate the meaning of comorbidity of different symptoms in the context of the general clinical picture. You should not rush: the diagnosis can become clear within 5 minutes, but also after 5 hours or 5 months. Diagnosis and patient rarely match perfectly: if you are not certain about the diagnosis, maintain a reflective attitude. The psychotherapist must “not hesitate to question” diagnostic hypotheses or those sent by the patient. Diagnostic conclusions should always be justified. A wrong diagnosis can harm the patient.

Dr. Allen Frances

In fact, psychotherapy is very present in the field of public health. According to WHO data, psychotherapy exists on all five continents and 250 million people have access to it. Worldwide, it is estimated that there are 700,000 psychotherapists. A very important component in the relationship between the psychotherapist and the patient is empathy.

Psychoanalysts know that the patient’s regression to unresolved conflicts will lead to creating conflicts with the analyst as a person, awakening childhood experiences with parents and others. This regression allows revisiting the sufferings, conflicts, and defenses of the past in the present. The analyst’s ability to thematize and articulate the patient’s childhood and current experiences is a crucial element in helping to reshape evolutionary distortions. A very important condition is empathy, emotional intimacy, i.e. the interpenetration of affective experience between the patient and the analyst. The analyst must show affectionate belief that the person’s suffering is real. It is essential that the analyst is able to address the regressed patient with words, tones of voice, and personal intentions animated by the desire to meet their emotional world while helping them articulate their subjective experience of the moment. The ultimate goal is that the truth discovered can give meaning to their life.

Now all those characteristics of the psychotherapist such as realistic optimism, good self-esteem, trust in human nature, and expectations of change, and the ability to withstand possible failures, can be summarized in a single word, which is love. “If love is not part of interpersonal relationships, nothing essential can be grasped about normal and sick existence: only love knows and makes someone know in their deepest dimension.” Being together in love thus finds roots in one’s humanity as a being constitutively oriented towards opening up to the other and giving oneself to the other, in its most essential, simple, and natural disposition to share not only space, existence, reality itself but to give all of oneself, to fill the existential void of the other with their own self.

Psychotherapy is only a specific model of reality and human nature with its own specific goals and “not” the “all-encompassing” or metaphysical model of all reality. Rather, there is a risk of falling into forms of reductionism such as immanentism, determinism. We can also say with the words of Sgreccia: “the risk of reductionism, well present in medicine, presents itself in all its dangers in psychiatry, when mental illness is addressed without adequate reflection on human reality and neglecting the intertwining of the bodily dimension with the mental and spiritual one.” Empirical studies are not sufficient to understand the human being. We can think of how psychology was initially a branch of philosophy, then it acquired its own identity when it positioned itself as an experimental science. This, however, has led to a loss of sight of the transcendent dimension of man, to focus exclusively on studying neurophysiological phenomena, in a repeatable and controlled manner, as is typical of experimental sciences. All this has resulted in an interpretation of psychic phenomena based on measurable and interpretable laws, which can be known precisely thanks to the method of positive sciences. Inevitably, this method has produced an idea of man devoid of that openness to spirituality and transcendence that is instead the constructive part of man. Here are the dangers when there is indeed a reductionist approach, when one focuses exclusively on the data that are produced with an empirical-experimental approach, which see at the end an equal clinical picture based on certain measurements, observations, results and completely disregard the patient with his/her lived experience and interiority. Therefore, they only focus on the illness.

In the therapeutic relationship, there needs to be an involvement that should not be simply trivialised over the course of the therapeutic relationship. It must start from a true encounter with the light of what a human being is – openness to others that must also be stimulated in the patient themselves. From an authentic encounter comes the knowledge of what are not just the problems, the difficulties that the patient can represent in a true dialogue, but there is also the possibility of knowing the resources on which to act so that the patient can open up to identifying where they have lost themselves and how it is possible to find themselves again. I repeat once again that the analyst’s ability to address the regressed patient with words, tones of voice and personal intentions animated by the desire to meet his emotional world while helping him articulate in words the subjective experience of the moment is important. The ultimate goal is that the truth discovered can give meaning to one’s life. Without God, man and his Self reach only a certain point:

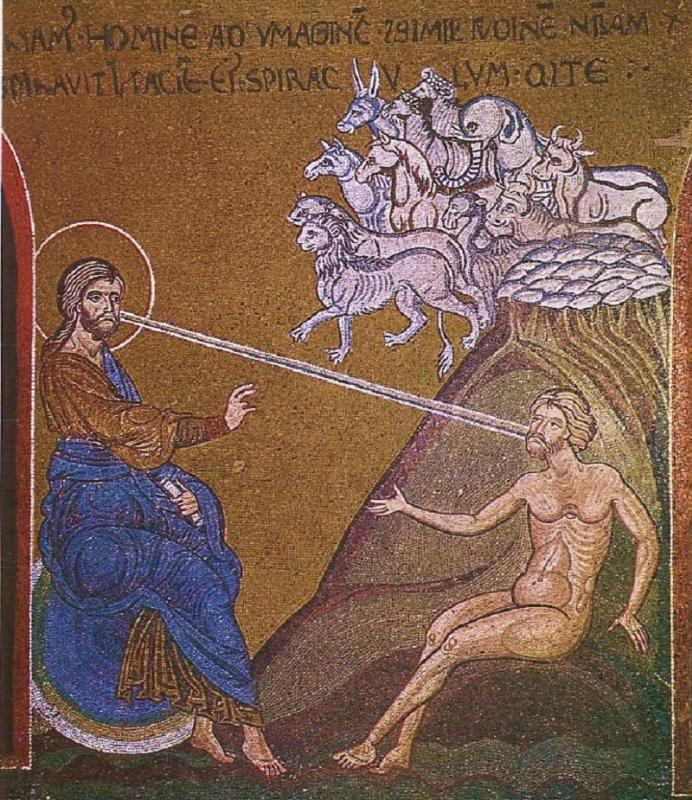

The Self that holds together the experienced and human behaviour contains cognitive, conative, affective, personal, and integration components. Further development depends on how I face the reality that is before me, without losing myself: how I balance the images I have made of myself and the world with new images, representations, and how much I am able to integrate new images with old ones. In this development, the Self is confronted with ethical and moral problems. I can find myself only if I ask myself the religious question in my personal history and in my reality, in which I experience myself as always united in the countless situations of my life. I understand the mystery of my Self only if I understand my entire life as a revelation of the divine mystery in the concrete conditions of my life. Only the religious dimension can embrace all the height, length, breadth, and depth of the mystery of God that is reflected and embodied in my Self because we are made in his image and likeness.

Therefore, the only anthropology and psychology worthy of man is the one that sees the foundation of being human in the orientation towards God and the values of the Gospel and in the possibility of realizing them. Any psychology that excludes this horizon risks thinking of the Self as excessively small and excessively selfish. I possess a freedom with which I decide for God, the Creator of life. In life, I become myself if my psychological development and religious development remain united with each other and stimulate each other. The Christian vision invites us to see ourselves in the countless joyful and sad events of our life as a mystery called to be transformed by mystery. The Christian vision allows us to experience ourselves in the physical and temporal limits of our life as a place where through the Spirit of God, what is great and unconditional is realized. The development of the Self can lead to two results: continuous growth in the dynamic of finding oneself. Or it can lead to the rejection of this truth.

Only those who are ready to lose themselves, to go beyond themselves and to make the gift of themselves, become themselves fully. The act of love towards one’s neighbors makes at least an implicit experience of God. In the gift made to the other, an infinite horizon of God as totally other opens up. Love between people is “The permanent exodus from the self closed in on itself towards its liberation in the gift of self and towards its rediscovery, indeed towards the discovery of God.

Being created in the image of God, being called to a communion of love with Him. This is not only a statement of Christian identity and belief, but also a prophetic message for postmodern and post-secular times. The fact that every human being, man or woman, is created in the image of God and inherently tends towards Jesus, who is the perfect image of God, is affirmed as a universally valid anthropological reality. Every person has within themselves a theocentric self-transcendence that is innate in every human subject.

Psychological and psychiatric work: Clearly, in our day and age, we find ourselves in the context of postmodern cultural reductions, reductionisms, and many other ideologies far from Jesus and the Gospel. We need to seek a bioethics, psychology, and psychiatry that, in its work, through scientific and existential help, tries to promote and centralise stable and dynamic growth and commitments in the logic of a freedom for the self-transcending love of individuals, families, and groups, modelled on the Gospel. In very simple words: If God and the Holy Spirit don’t help you with grace to be a good psychologist or psychiatrist, you will only get to a certain point and then lose strength. The starting point is always the person as such, seen from the perspective of the child of God the Father and brother in Jesus Christ. Therefore, psychological and psychiatric and psychotherapeutic methods must, with the help of God, promote a more stable and meaningful growth of self-transcending freedom and love. Psychotherapeutic processes can become paths towards the objective truths of being created in the image and likeness of God, who is Jesus Christ.