by Gideon Lazar

I. Introduction

Metaphysics was the primary lens through which people before modernity understood the world. It provided the framework in which they discussed every other issue. One of the most overlooked metaphysical systems is that of St. Maximus the Confessor. Maximus was a seventh century Byzantine monk. In his work the Ambigua, Maximus articulates his understanding of the metaphysical structure of the universe and God’s plan for it. “Ambiguum 7” is one of the key chapters to understanding this system. In it, he articulates the overall structure of the history of the universe in metaphysical language.

This work was not written in a vacuum though. The Ambigua to John, the part of the Ambigua that contains “Ambiguum 7,” was written as a response to the Origenists. The Origenists were a group of Christians who followed the teachings of the third century Christian theologian Origen. They alleged the preexistence of souls and the salvation of all mankind, among many other things. Maximus argued these beliefs were heretical and contrary to reason.

In order to respond to the Origenists, Maximus returns to the shared tradition of pre-Christian philosophy, especially the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle. Metaphysics had already been studied for around a millennium in the Greek speaking world and had developed into a large body of ideas and terminology. Maximus freely borrows and rejects what he likes, forming it into a Christian metaphysics.

Maximus is not merely arguing that the Origenists are wrong though. He is positing a way to understand all of existence. God created the world in the beginning as a reflection of the Son and we are all obligated to order ourselves to Him, so that in doing so, we will rise up to him until eventually we can even in some sense be said to become God ourselves, although only by grace and not by nature. This movement means that history at the large scale is linear, moving from creation to rest in God.

The rest of this paper will break down the context of Maximus’s argument in “Ambiguum 7,” as well as what the argument itself is. Section II will examine the historical background of Maximus’s life. Sections III-IV will examine the pre-Christian philosophical concepts that underlie Maximus’ own metaphysics. Section V will examine the beliefs of the Origenists. Section VI will examine Maximus’ response. Sections VII-X will then examine Maximus’ own four-part metaphysical framework for understanding the history of all of reality. Section XI will finally conclude with a summary and a discussion of the importance of Maximus today.

II. Historical Background

It is difficult to reconstruct Maximus’ life due to the paucity of sources about his life. There are essentially only two medieval sources on Maximus’s life. [1] The first is an account in Syriac written by a Monophysite cleric from Jerusalem. Although he was contemporary with Maximus’s own life, it was essentially an attack on Maximus’ character. The more positive portrayal of him comes from a later Greek hagiography. Despite these problems though, many facts about his life can still be established with great certainty.

His early life is especially uncertain. [2] The Syriac account says that Maximus was an illegitimate slave child. However, the Greek account says that Maximus was born to a noble family. A number of passages in Maximus’s own writing, as well as his wealth of knowledge in general, suggest this latter account is more likely. Whatever the case though, it is clear that Maximus quickly entered the monastic life. At some point into his time as a monastic, Maximus moved to North Africa, although the exact details of the move are unclear. [3]

It is at this point that Maximus authored the Ambigua to John. [4] A short while after Maximus left Asia minor, a former friend of his, John of Kyzikos, sent a letter to Maximus. In it, he listed many quotes from St. Gregory the Theologian, more commonly known in the West as St. Gregory Nazianzen, which were being used by Origenists. [5] Maximus wrote an explanation of each one. However, each ambiguum is not merely an explanation of what Gregory said. Rather, Maximus uses these quotes as starting points to discuss complex theological and philosophical problems.

Maximus’s own fame would not come from his involvement with refuting Origenism, which had already been condemned at this point, but with his refutations of Monoenergism and Monothelitism. [6] These two closely connected heresies asserted that Christ has only one activity and one will. They were highly promoted by Byzantine emperors as a way to reconcile the division between Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian Christians in the empire. Maximus wrote vigorously against these heresies.

One of his works against monoenergism was the Ambigua to Thomas, once again defending the orthodoxy of St. Gregory the Theologian against heretical interpretations. [7] Since activity and motion are so closely tied, Maximus combined the two ambiguae into the Ambigua. [8] The Ambigua to Thomas’ discussion of activity in God serves as a prologue to the Ambigua to John’s discussion of motion in God. The former also lays out proper Christology, while the latter explores the mystery of God more deeply. Together, the two serve as a singular work on the metaphysics of God and all of reality.

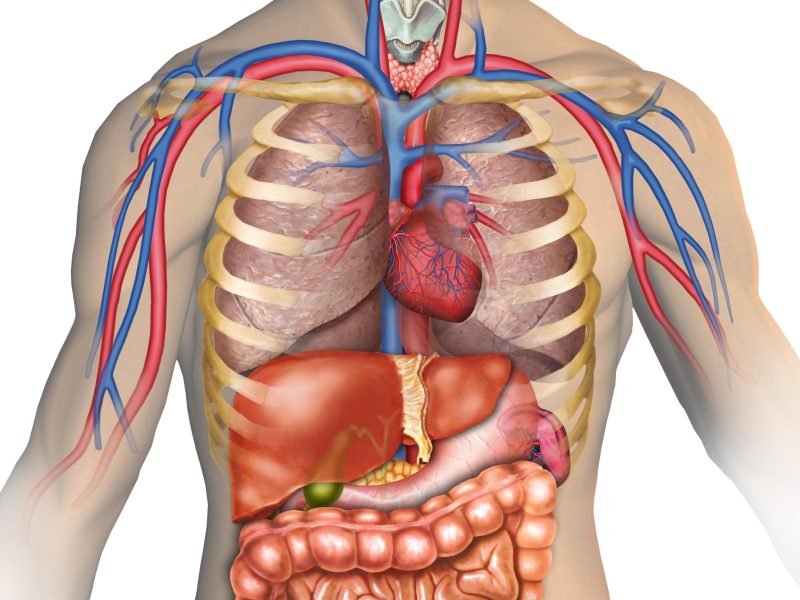

Maximus’s theology was not universally accepted in his own lifetime. While a council in Rome, which it is unclear if he attended, endorsed dyothelitism, the emperor refused to accept its decrees. [9] Maximus was called to two trials in Constantinople, but refused to recant his beliefs. He declared the emperor a heretic with whom he would not commune. Maximus had his right hand cut off and his tongue cut out so he could no longer write or preach against Monothelitism. [10] He was forced to spend the rest of his life in exile in solitary confinement in Georgia but died less than a year later. His theology was ultimately vindicated though, and his theology was dogmatized at the sixth ecumenical council in AD 681. [11]

Maximus has his hand and tongue cut off

III. Motion in Pre-Christian Philosophy

Before Maximus’s own philosophy can be analyzed, it is important to look at the pre-Christian roots of many of his terms and ideas. The origins of Greek philosophy are heavily rooted in debates about motion (κίνησις). By motion should be understood not merely change of location, locomotion, but all forms of change. There were two main views of motion in presocratic philosophy, the Eleatics, most notably Parmenides and Zeno, and Heraclitus. [12] The Eleatics rejected all possibility of motion. [13] According to Parmenides, there is only being. While the Eleatics presented many logical arguments for their view, it only raised more problems as it contradicted basic observation. Heraclitus responded to the Eleatics by taking the opposite view. [14] There is no stability whatsoever, only motion. However, this view also came with the opposite problem as now it could not account for the observation that there are times when things are not changing.

Plato responds to these two positions in the Sophist. He argues from observation that there is both motion (κίνησις) and rest (στάσις). [15] Being is instead distinct from motion because it cannot be identified with either one, nor is it the combination of them. [16] While Plato discusses the distinction between motion, rest, and being, he does not expound upon what exactly they are or what their relation is. [17] This task in the evolution of philosophy would fall upon Aristotle. He takes it up in Metaphysics IX. [18]

Aristotle expands upon Plato’s category of being by dividing all being into the categories of potentiality (δύναμις) and actuality (ἐνέργεια or ἐντέλεχεια). [19] While Aristotle does accept that these terms can be used in many ways, it is most important to understand their use with reference to motion. Aristotle defines potentiality as the state of having the power of “acting and being acted upon.” [20] Potentiality is when something has the possibility to become something else, either by itself or by something else. Aristotle gives the example of a block of wood. [21] The block of wood has the potential to become a statue according to Aristotle because it could be shaped into a statue. Therefore, with relation to the statue, it is in a state of potency. On the other hand, the state of actuality is when something is fully what it is. So, the statue would stand in actuality with respect to the block of wood. Something can be in both act and potency at the same time, being in potency with respect to one thing and act with respect to another.

Motion, then, is the movement from potency towards act. [22] To apply this to the earlier example, carving would be the motion in which a block of wood moves from its potential and becomes actually a statue. Aristotle makes the important distinction between motion and actuality by pointing out that motion is incomplete, while actuality is complete. Once the block of wood is a statue, it is no longer in motion. He uses time to help make this distinction. [23] Motion occurs over a period of time while actuality is a discussion of what is now.

In addition, all motion is movement towards some end (τέλος). [24] This end is what actuality is. A thing starts in potentiality and moves towards actuality. The actuality towards which it moves is the end proper to its nature. It is the movement towards the ends which are inherent in a nature which is the cause of motion.

This distinction between potency and act was created by Aristotle to solve the problems raised by Parmenides and Heraclitus. [25] Motion is not a change from non-being to being, but from being in potency to being in act. Likewise, there can be stability because motion is not being itself, but a change of one form of being to another. Motion therefore requires stability.

Aristotle also introduces other principles to explain motion. He explains that things have ends towards which they move because “everything which is generated moves towards a principle, i.e. its end.” [26] By generation (γένεσις), one should not understand coming into being out of nothing, but rather coming into being from some other thing which has corrupted. Aristotle believes the world to be eternal and does not have a conception of creation ex nihilo. [27]

Aristotle expands upon motion in Metaphysics XII by connecting the motion of things to the divine. [28] There must be some first cause in order for there to be motion at all. [29] However, if this first cause moved, it would itself need something to move it. Aristotle reasons therefore that there must be an unmoved mover. This mover moves things as the object of desire. [30] The prime mover is fully actual, and therefore supremely good. The rational will desires this good, and so the heavenly bodies move out of love for the prime mover. [31] This starts a chain by which all things in the universe move. Therefore, the end towards which all things move is ultimately the prime mover. [32]

Aristotle call this prime mover God. [33] However, this is not a personal God. While God, according to Aristotle, does think because thinking is the highest possible activity, He only thinks of Himself. If He thought of something else, that thing would be less actual than Him and thus His thoughts would be less actual. In order to have no potency, God must only think of that which is most actual, Himself.

Aristotle’s concepts of potency, act, and motion would remain important throughout the history of Greek philosophy. One important development in it though was the introduction of secondary meanings for δύναμις and ἐνέργεια, power and activity, respectively. [34] δύναμις became the power something has to perform a certain activity. ἐνέργεια became a type of motion, an activity. This did not lead to a loss of the original senses of the words though. Indeed, the new use is still analogous to the original use as a power is a form of potency and an activity is an actualizing of a power. While both uses of δύναμις and ἐνέργεια remain in Maximus, he tends to favor the latter use. [35]

Plato and Aristotle dispute the location of the forms

IV. Procession and Return in Pre-Christian Philosophy

The other core element of classical metaphysics is the idea of procession (πρόοδος) and return (ἐπιστροφή). This idea is rooted in Plato’s cosmology. In his dialogues, Plato posits a heavenly realm of forms (εἴδη) that exists eternally. The highest of these forms is the Form of the Good, which is the source of all the other forms. A being known as the Demiurge at some point in time took matter and created the world after the model of these forms. [36] The soul also preexisted with these forms. Humans gain knowledge then by remembering the forms in things from their preexistence. Plato especially emphasizes this as the job of the philosopher. After death, the soul returns to the world of the forms. [37] While Plato does not explicitly develop an overall system of procession and return, the fact that souls do proceed from a celestial realm and return to it would be developed by later interpreters.

The most immediate influence of this system was from the theory of forms. Aristotle does keep the concept of form, but he instead places the forms of things in the things themselves rather than in a heavenly world of forms. [38] However, Aristotle does not develop an idea of the preexistence of souls or their immortality.

A reconciliation of Platonic and Aristotelian forms would come in Neoplatonism. For Plotinus, the forms exist both in the divine Intellect and in the material things themselves. [39] The Intellect is an overflowing of the One, which is Plotinus’ development of Plato’s Form of the Good. This was the underlying metaphysics for Plotinus’ development of the doctrine of procession and return. All things proceed from the One as the beginning of all things and return to the one as the end of all things. [40] Thus the beginning and end (ἀρχή and τέλος) are the same in Neoplatonism. While matter is not evil in Neoplatonism, it is inferior to the spiritual because it is a potency which proceeds from the One. [41] Thus, like all things, it will eventually be subsumed back into the One.

Origen

V. Origenism

This concepts of the preexistence of souls, their procession out from the One, and their return to the One had a great impact on Christian thought. One early Christian Platonist was Origen. [42] Origen lived in the third century. While he claims to base his reasoning on scripture, his interpretation of scripture is very influenced by Platonism. In his work De Principiis, Origen argued that before the creation of the world, souls preexisted with God in spiritual bodies. [43] These souls then descended into material bodies as a result of sin. Origen argues that this also explains motion in the word.

What other cause, as we have already said, are we to imagine for so great a diversity in the world, save the diversity and variety in the movements and declensions of those who fell from that primeval unity (ἑνάδος) and harmony in which they were at first created by God. [44]

Origen did believe though that eventually everything will be restored to how it once was, the ἀποκατάστασις. [45]

Origen often wrote in a very elusive style, leading to unclarity in what exactly he meant by many things. [46] Of primary importance though were the later followers of his ideas, the Origenists. While many writings of Origen were influential upon orthodox Christianity, his writings were not accepted wholeheartedly like they were by the Origenists. The Origenists take Origen in a very literal sense. They especially emphasize the primordial unity of all rational beings. [47] This is really the lynchpin of their philosophical system. Everything once lived in a perfect unity with God as a collection of identical intelligences. Some sinned and fell away from God, and as a result became trapped in bodies. Through Christ, all would return to this perfect original state. Without this initial unity, the rest of the system falls apart. It is important to note that the Origenists themselves rarely used the word unity (ἑνάς), but the term became common in writings against Origenism regardless as it was a useful and accurate description of their system. [48]

While Origenist idea had long been treated as heretical, they were not formally condemned until the sixth century in response to their revival. [49] Their first formal condemnation was by the emperor Justinian, who issued an edict against them in 542. [50] Origenism was also again condemned under Justinian in the canons of the fifth ecumenical council in 553. [51] It is unclear if the council itself actually included the 15 canons against Origen, but it is clear that they quickly became treated as such. [52]

Emperor Justinian I

IV. Maximus’s Response to Origenism

As explained in section II, many Origenists used the writings of St. Gregory Nazianzen to justify Origenism. Gregory was considered to be one of the highest theological authorities in the Byzantine Empire by the seventh century, being held to nearly the same authority as scripture. [53]Gregory’s ambiguities from his rhetorical style often allowed for Origenist interpretations. As a result, Maximus authored the Ambigua to John. [54] In it he takes unclear passages from Gregory that were given to him by John of Kyzikos. While Maximus did read Origen, it is unclear if he had done so before writing the Ambigua to John. [55] Maximus’s understanding of Origenism seems to most heavily be drawn from Justinian’s two sets of condemnations.

“Ambiguum 7” is especially focused around deconstructing the Origenist account of procession and return. Maximus defends the orthodoxy of a passage of Gregory in which he describes man as “a portion of God that has flowed down from above.” [56] This passage is very Origenist in its language, so it is clear how it could pose a problem of interpretation for orthodox Christians. [57]

Maximus recognizes four key elements in the Origenist account: (1) “there once existed a unity (ἑνάδα) of rational beings… with God,” [58] (2) “a ‘movement’ (κίνησιν) that came about,” i.e., the fall into sin, (3) “the creation of this corporeal world so that [God] could bind them in bodies as punishment for their former sins,” and (4) that everything will again be as it once was, the ἀποκατάστασις. [59]

Although Maximus is responding to other Christians here, he recognizes the source of Origenist doctrine is not in Christianity but in paganism. [60] He sees his opponents therefore as more pagan than Christian. While Maximus does draw heavily from pagan metaphysics, although only occasionally acknowledging it, [61] he will seek to Christianize it, only adopting the metaphysical principles but not the Platonic origin myth itself.

Maximus first responds to the Origenist account procession and return of souls. He points out the logical impossibility of such an account. Maximus’s argument is very reminiscent of Aristotle, especially Metaphysics XII. Maximus points out that “the good” (καλόν) is the end of human desire. [62] By “the good,” Maximus is referring to God Who is the highest good. As in Aristotle, there is a motion towards God because God is the highest good and the good is what we desire. Maximus also points out that a thing comes to rest when it finally reaches what it desires. This implies the underlying Aristotelian metaphysical principle that final cause is the most important cause of motion. Once this final cause has been accomplished, there is no longer anything causing the motion. Thus, beings abiding within God would be at rest because they have already reached the final cause of all things. If in the original state then beings abided in God, there would be nothing that could cause them to go into motion in the first place.

The Origenist objection to this would be that sin caused there to be an initial motion away from God. This does not fix the problem though as Maximus points out. In that case, there should be nothing to change their motion away from God because they already rejected abiding in God and there is no higher good. [63] There can now be no return to God, but only an eternal procession away from God. Either the Origenists must reject the procession from God or the return to Him.

Some Origenists may attempt to reconcile the two by arguing that people’s experiences of being away from God would cause them to repent and return to God. This creates an even bigger metaphysical issue for many reasons. Firstly, beings now love the good “not for its own sake, but because of its opposite.” [64] The final cause of these people would now be fear of the bad rather than love of the good. If God is not the highest good, then He would cease to be God. The entire foundation of theology has now been destroyed.

Secondly, this would still stop there from being a true return to God. If God is no longer the highest good, then He “would not attract all motion” because He is no longer the final cause of all things. [65] God must be the final cause of all things in Himself and not because of anything else if there is to be a return.

Finally, Maximus points out that this places evil as metaphysically prior to good. [66] It is only because of evil that there would be a return, and so evil was necessary to create the good state of rest in God. Evil is now the cause of good rather than the mere absence of good. Furthermore, since it was evil that encouraged them to return to God, this means the absence of God, evil, is even more powerful than God Himself, the good.

Although the primordial unity is clearly identified by Maximus as the key problem with Origenism, [67] he also responds to its other major problem, the preexistence of souls. [68] He leaves this refutation to the very end of “Ambiguum 7,” showing that he considers this point to be of little importance in the overall Origenist metaphysics. It is simply a result of the doctrine of the primordial unity rather than an axiom in its own right.

On the relationship of body and soul, Maximus breaks from the Aristotelian tradition of the soul as the form of the body. [69] Instead, Maximus consider them to be one form together. [70] Maximus does consider the body and soul to be related, but as parts to a whole. There is only one form, the form of “the whole human being.” He elsewhere calls this form the ὑπόστασις. [71] It is likely then that Maximus’s Cappadocian trinitarian theology leads him to consider there to be a unifying subsistence as the form rather than just the soul.

Maximus identifies two problems with the preexistence of souls. First, he points out that there would not be a continuity between the person in the primordial unity and the person in the body. [72] If the form of the soul were to merge with the form of the body at the fall to create the embodied person, then this would be a new form. Since the form is what the thing is, it would no longer be the same thing. The soul would not maintain an essential continuity with the new person because there is not the same essence shared by the two; the continuity would only be accidental. The Origenists may respond that the soul does not change forms by gaining a body, but rather that it is the nature of the soul to come into a body. [73] Maximus points out that if the nature of the soul is to come into a body, then it would keep changing bodies because something that is a certain way by nature will continue to act according to its nature. Since people do not change bodies, this must be false. [74]

Secondly, if a person were merely his soul, then there would be no way to distinguish one person from another. [75] A body has certain things to distinguish it from another body, specifically temporality (πότε) and location (ποῦ). These categories of relation and distinction are once again drawn from Aristotle. [76] The Origenist may object that since the soul and body do separate at death, and therefore Maximus should fall into the same problem. [77] However, even after death the soul and body still have a relation to the original whole of the person as there was still at one point in time a whole person. Therefore, they are not soul and body “in an unqualified way” because they only continue to be soul and body in this relation and not as they are now. Maximus therefore distinguishes their “being” (οὐσίας) from their “generation” (γενέσεως). [78] As long as a person has a body at generation, they will always exist as a person in relation to that origin. In fact, it is this distinction between being and generation that will serve as the basis of Maximus’s own metaphysics.

VII. Maximus’s Alternative Metaphysical Account

Maximus’s own metaphysics are based on the distinction between beginning and end. The beginning state is not the same as the end state. While paganism sees history as essentially cyclical, Christianity holds history to be, at least in the big picture, linear. Before all of creation there was just God, and at the end of history all the saints are with God. Thus, there cannot be an ἀποκατάστασις because things have changed between the beginning and end state. Instead of the pagan notion of the eternal existence of all things, history now begins for Maximus with the creation of all things “ex nihilo (τὸ ἐκ μὴ ὄντων).” [80] Likewise, history does not end with the destruction of matter, but rather its incorporation into the divine life. [81]

This is not to say that Maximus rejects the concept of procession and return entirely. Creation ex nihilo and divinization are a procession and a return, respectively. But they are not a procession and return in the absolute sense since they do not start an end at the same point. Rather, they are a procession and return from and to God, and specifically Christ. Maximus quotes the book of Revelation to call God “the beginning (ἀρχὴ) and the end (τέλος).” [82] While Maximus here is speaking more philosophically and so refers to God, this passage in scripture is spoken by Christ about Himself. For Maximus, the procession and return are fundamentally Christocentric. [83] In other works, Maximus places the fundamental turn from motion away from God to motion back towards God as the crucifixion and resurrection. [84] Maximus argues that Christ “recapitulates (ἀνακεφαλαιούμενον) all things in Himself” because He is the beginning, middle, and end of the procession and return. [85]

It is this Christocentric and linear procession and return that gives Maximus his four main points to respond to the four Origenist points. [86] In response to the henad, point one, Maximus brings in a Platonic conception of the forms, which he calls the λόγοι, so that the ideas of all things exist eternally in Christ, even if they do not preexist actually. Maximus responds to points two and three, the beginning of motion through sin and the creation of the material world as a result of it, by flipping their order. Maximus begins history by the creation of the material world and then moves from there to the origin of motion as the natural result of generation. Finally, while Maximus generally agrees with the Origenists on the end state, point four, he emphasizes the material existence of the end state, although not as it is now, but infused with the divine activity (θεία ἐνεργεια) so that all things become divinized (θέωσις).

VIII. The Λόγοι

While Maximus seeks to refute the concept of a primordial unity, he does not entirely throw out the idea. [87] He does see a need for there to be some type of preexistent rest. [88] After all, God is eternally perfect. To respond to this problem, Maximus draws in the Neoplatonic conception of forms and Christianizes it. The form of a thing exists both in a heavenly location and in the thing itself. While for Plotinus this is the divine Intellect, [89] Maximus places the forms in Christ.

The Christianization of Neoplatonic forms had already begun before Maximus. Dionysius describes the forms as ideas which emanate out into the world. [90] He also calls them the “divine wills.” [91] John of Scythopolis further develops this by making these ideas the thoughts of God which are identical to his essence. Maximus, possibly drawing on Origen, identifies them specifically with the person of Christ. [92] This allows Maximus to make an association between the “one Λόγος” and “many λόγοι.” [93] Christ is called the Λόγος by scripture, [94] and so Maximus explains this by identifying Him with the λόγοι, the rational principles of things. In fact, Maximus exclusively calls the forms the λόγοι. Whenever Maximus speaks of form (εἶδος), he is only using it of particular things. [95]

Drawing on John of Scythopolis, Maximus identifies the many λόγοι as identical to the one Λόγος. [96] However, the plurality of the λόγοι is not the result of creation, but they are in some way distinct from each other. Each created thing in a different way reflects and participates in Christ. [97] This will be essential for how Maximus understands all things to be redeemed in Christ.

While the λόγοι of things preexist in God, it is only these universals which preexist. By contrast, Maximus says that, “individual things were created at the appropriate moment in time, in a manner consistent with their λόγοι, and thus they received in themselves their actual existence as beings.” [98] There is some sense though in which the things themselves can be said to preexist in two way. First, Maximus does grant a preexistence “in potency (δυνάμει),” just not “in actuality (ἐνεργείᾳ).” [99] In using this Aristotelian distinction, Maximus is not denying all preexistent being to them, but is limiting it to the qualified sense of potency.

Secondly, Maximus grants that they preexist as the will of God according to which all things were created. [100] This also solves a major issue in classical philosophy. In Metaphysics XII, Aristotle argues that God does not know anything but Himself because if He thought about something lower, He would cease to be most actual and thus cease to be God. [101] Maximus agrees with much of the logic of this argument. He denies that “God knows intelligible things by intellection, and sensory things by sensation” but “it is not possible… that He who is beyond all being should know beings in a manner derived from beings.” [102] However, Maximus has the additional metaphysical tool which Aristotle lacked, the λόγοι of created things as identical with God. In knowing Himself, God knows all “beings as His own wills.” This is not to say these beings actually exist in God, but rather only that God knows them through His own existence and His own will.

The Father knows the world through seeing the λόγοι of what he wills to create in the Son

IX. Generation and Motion

The Origenist order of motion and then the generation of matter are inverted by Maximus. Instead, like Aristotle, Maximus affirms the priority of generation to motion. [103] Something must come into being in order to be able to move. The only thing which is preexistent is God, and, as a result, He has no motion. [104]

By inverting this order, Maximus is able to get at one of the central points of Origenism, the inherent badness of matter and motion. Motion for the Origenists is at its root a motion away from God. Likewise, matter is the result of sin for the Origenists. Maximus does agree with the Origenists on the superiority of rest and the spiritual over motion and the material. However, motion and the material are still inherently good because they are ordered to rest and the spiritual. [105]

Balthasar points out that in Maximus “motion (kinesis) is no longer seen simply (in Platonic fashion) as a sinful falling away but is seen (in Aristotelian fashion) as the good ontological activity of a developing nature.” [106] The Origenist myth is Platonic in origin. While there are certainly still strong elements of Platonism within Maximus, Maximus tends to lean more heavily on Aristotelian conceptions of motion, potency, and act. Drawing from this Aristotelian system, Maximus connects the nature of a thing with its motion. When something is generated, its nature has a “natural power (δύναμιν φυσικὴν)” according to the λόγος of its nature. [107] This then actualizes into motion as an “effective activity (ἐνέργειαν δραστικὴν).” Motion is the movement from potency to act of a nature. Likewise, all motion is ordered to “its proper end (τὸ κατ’ αὐτὴν τέλος).” Since generation is the cause of motion, that which generated all things, God, is the cause of these ends. Drawing on Aristotle, Maximus argues that the end of all things must be God since he exists “for the sake of nothing.” Beings therefore finally come to rest in God. [108]

This Aristotelian reframing of motion answers the Origenists. It flips of Origenist triad of “στάσις-κίνησις-γένεσις” to “γένεσις-κίνησις-στάσις.” [109] Generation causes motion, so a preexistent being could not come into motion. Likewise, motion is ordered towards God, and so the first motion of things could not possibly be motion away from God.

Maximus is now left with the problem of why there is still motion away from God though. Sin is self-evident in the world, and so he must answer this problem presented by the Origenists. His solution is free will. [110] As rational beings, humans have the choice to move towards God or away from Him. The important difference with Origenism though is that humans have not at some point in the past existed in the presence of God, and so as long as humans exist in motion, they can direct their motion as they wish. At the end of time though, all things will have reached their end and so there will no longer be any motion. The Origenists start history at this point, and so they cannot explain the start of motion. Generation as the source of motion solves this problem.

It also creates a moral imperative. Maximus says that “from the same source whence we received our being, we should also long to receive being moved.” [111] Humans are generated ordered to God, and since they have the free will to choose in which direction their motion is oriented, they should choose to make their motion in line with their generation. To do otherwise is to go against human nature. The Origenists however cannot create this same moral imperative because they place free will before generation.

For Maximus, the motion of a human is ideally linear. He should come into being, then move along with the direction of his generation, and then come to rest in God. The Origenist on the other hand affirms a necessarily cyclical motion. All things start and end with God. Origenism therefore rejects free will in anything but a temporary sense. All humans are saved as part of ἀποκατάστασις. For Maximus though, it is up to the free will of the human as to whether or not he chooses to have his motion towards God. Since Maximus denies that the beginning and end is the same, he does not need to affirm universalism.

The Church Fathers understood the transfiguration, where Christ manifested the divine glory to the apostles, to be the prototypical example of divinization

X. Divinization

Maximus’s understanding of this end state is based on his philosophy of motion. Since all motion is ordered towards God, it has its rest in God. [112] For the Origenists, this rest is the inactive rest which existed before creation. However, Maximus allows for there to be activity within this eternal rest at the end of time. This activity is the divine activity.

While a being moves by their own activity in this age, this will not be the same at the end of time. Rather, “it will have received the divine activity (θείας ἐνεργείας).” [113] While at first it would seem that this violates the nature of what rest is, since there is no motion within God, Aristotle says out that ἐνεργεία, when used as actuality, is not itself motion but the end of motion. Maximus has brought together these two senses of ἐνεργεία when speaking of God.

Maximus says that to receive the divine energy is to “become God by divinization (θεώσει).” [114] While Maximus does not explain why this is in this ambiguum, it can be understood by a comparison with “Ambiguum 2” where Maximus says that “the principle of natural activity is what defines the essence of a thing, and as a rule characterizes the nature of every being in which it adheres.” [115] An activity is the actualization of a natural power, but it is only the activity which can be sensed by other beings. It is by the activity of a thing that one comes to know what powers it has, and therefore what its essence is. All perceptible aspects of a beings are activities because all accidents of a things are actualizations. In this quote from “Ambiguum 2,” Maximus is explaining why Christ must have a human activity to truly be human. His human activity is how one can know He is human. While the saint does not actually come to possess a divine essence, the saint does become God in the sense that he is now known by the divine activity. Maximus therefore explains divinization by explaining that the saint “will no longer be able to wish to be known from its own qualities, but rather from those of the circumscriber, in the same way that air is thoroughly permeated by light, or iron in a forge is completely penetrated by fire, or anything else of this sort.” [116] All the activities of the saint come to be divine, and in this sense the saint becomes God because he ceases to have an activity proper to his nature.

One concern with such a theology is that it would destroy the integral being of what it means to be human. Maximus points out though that taking on the divine activity is not “the destruction of our power of self-determination, but rather affirming our fixed and unchangeable natural disposition.” [117] Genuine free-will is not merely the ability to choose between good and evil, but the ability to choose between many goods. What it means to be human is to be ordered towards God. Therefore, the end of being is to take on the divine activity. The divine activity perfects and elevates human nature rather than destroying it.

Since human nature is divinized, it means that the whole of the human person that is divinized, both body and soul. Unlike the Origenist conception in which there will only be a spiritual matter at the end, Maximus affirms the real existence of matter in the age to come. This is because he is not forced to make the end just like the beginning. However, matter does not remain simply as it is in this age. Rather, all matter will become divinized, which means that for humans “the soul will receive immutability and the body immortality.” [118] Unlike the Origenists who see matter as evil, Maximus is able to affirm the goodness of matter because it was not created as a punishment for sin. Matter is the good creation of God and so in the end God perfects and elevates matter. Man remains human by nature but is entirely made God by his elevation. [119]

This redemption and elevation of the entire creation is done in and through the person of Christ. As mentioned in section VII, Christ “recapitulates (ἀνακεφαλαιούμενον) all things in Himself.” [120] Maximus is therefore able to refute the Origenist use of “portions of God” in Gregory Nazianzen in two ways. Just as all beings “are called ‘portions of God’ because of the λόγοι of our being that exists eternally in God,” [121] so also Christians specifically are called portions of God because they “are the members and the body of Christ.” [122] Christians can be considered portions of God therefore in two different ways. All beings are portions of God insofar as they participate in the person of the Son as the Λόγος, but they are also portions of God insofar as they participate in the person of the Son as he is redeemer. The entire universe therefore naturally reflects Christ, but through its divinization, which comes through His incarnation, death, and resurrection, it comes to reflect Him to an even higher degree.

XI. Conclusion

Maximus stands within a larger tradition of philosophy going back to the presocratic philosophers. He takes what is good within this tradition and develops it into a Christian system of metaphysics. This allows him to respond to the Origenists regarding the primordial unity of beings. The Origenists alleged a four-step metaphysical history of unity, sin, falling into bodies, and the return of all things to as they were. Maximus shows why such a system is logically contradictory, and instead proposes that the four steps be the preexistence of the λόγοι, the creation of a good world by God, the movement of man both to and away from God, and then the eventual rest of all beings either as deified or damned. This involves a transformation of the world from the beginning to the end, resulting in a linear rather than circular view of history. He also places Christ at the beginning, middle, and end of this line. Christ is the Λόγος, creator, sustainer, redeemer, and end of this world.

It is easy to see the issues at play here as totally foreign to the modern world. Maximus understands words like motion and actuality in a totally different way than most modern people. As a result, it is easy to treat the study of Maximus purely in historical terms. Indeed, even the structure of this paper has assumed a historical orientation. It is not entirely wrong to read Maximus in his historical context, but he ought to be read in the same sense he understood history to be. For example, many scholars object to considering Maximus as a proto-scholastic merely because of scholasticism developed partly out of his thought. [123] However, this is to read Maximus in a light he would not have seen his own work. Maximus viewed history as a development of the world’s ascent to God. If he had been able to see the future, he certainly would have viewed his own writings within the larger tradition both before and after, and so it seems that he would not have rejected the title of proto-scholastic except out of his humility.

The study of Maximus should also not be limited to a sort of historical anthropology though. What Maximus offers to modern people is a return to a more metaphysical way of seeing the world. While the terminology is foreign, the fundamental issues being discussed are still very relevant. The creation of the world, the relation of the soul and body, the goodness of matter, the direction of history, and other issues are still worth discussing. Perhaps modern philosophy has lost the tools needed to discuss these issues, and so perhaps Maximus must be rediscovered to answer these age-old questions.

Notes

[1] Paul M. Blowers, Maximus the Confessor: Jesus Christ and the Transfiguration of the World, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 25-26.

[2] Blowers, 26-27.

[3] Blowers, 28-31.

[4] Nicholas Constas, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, vol. 1, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), x.

[5] Constas, x-xvi. See section V for more about Origenism.

[6] Blowers, 42-54.

[7] Constas, xx-xxii.

[8] See section III.

[9] Blowers, 54-63.

[10] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Cosmic Liturgy: The Universe According to Maximus the Confessor, trans. Brian E. Daley, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003), 80.

[11] Blowers, 62-63.

[12] Edward Feser, Scholastics Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction, (Piscataway: Transaction Books, 2014), 34.

[13] Feser, 34-36.

[14] Feser, 36-37.

[15] Plato, Sophist, trans. Harold North Fowler, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1921), 250A.

[16] Plato, 250C.

[17] A. E. Taylor, Plato: The Man and His Work, (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2012), 388-89.

[18] Aristotle also discusses motion in Physics VI, although the two discussions are nearly identical in content; c.f. David Bradshaw, Aristotle East and West: Metaphysics and the Division of Christendom, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 7-12.

[19] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 2 vol., trans. Hugh Tredennick, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1933-1935), 1045b33-46a4.

[20] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1046a20-21.

[21] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1048a33-35.

[22] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1048b18-36.

[23] Bradshaw, 9-12; c.f. Aristotle, Eudemian Ethics, trans. H. Rackham, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1935), 1173a34-b4.

[24] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1050a8-11.

[25] Feser, 36-39.

[26] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1050a8-9.

[27] “But motion cannot be either generated or destroyed, for it always existed; nor can time, because there can be no priority or posteriority if there is no time. Hence as time is continuous, so too is motion; for time is either identical with motion or an affection of it.” Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1071b6-11.

[28] c.f. Bradshaw, 24-44.

[29] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1071b12-72a19.

[30] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1072a26-b2.

[31] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1073a26-b4.

[32] This should be understood not only as final cause though, but also as an efficient cause by means of a formal cause. Bradshaw, 29-32, 39-42.

[33] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1072b14-31.

[34] c.f. Bradshaw, 45-96.

[35] This is likely under the influence of the Cappadocians who also favor this use. c.f. Michel René Barnes, The Power of God: Δύναμις in Gregory of Nyssa’s Trinitarian Theology, (Washington: The Catholic University of America Press, 2001), 260-307.

[36] Torstein Theodor Tollefsen, The Christocentric Cosmology of St. Maximus the Confessor, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 23-25.

[37] Taylor, 183-89.

[38] Tollefsen, 25-26.

[39] Tollefsen, 27-33; Balthasar, 115.

[40] Tollefsen, 72-74.

[41] Gerd Van Riel, “Horizontalism or Verticalism? Proclus vs Plotinus on the Procession of Matter,” Phronesis 46, no. 2 (2001): 132-38.

[42] Mark J. Edwards, “Origen,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, rev. April 18, 2020, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/origen/.

[43] Sophie Cartwright, “Soul and Body in Early Christianity: An Old and New Conundrum,” in A History of Mind and Body in Late Antiquity, ed. Anna Marmodoro and Sophie Cartwright, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2018), 179.

[44] Origen, De Principiis, in Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 4., trans. Frederick Crombie, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, rev. and ed. Kevin Knight for New Advent, (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1885), http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0412.htm, 2.1.1; c.f. Polycarp Sherwood, The Earlier Ambigua of Saint Maximus the Confessor and His Refutation of Origenism, (Romae: Pontifium Institutum S. Anselmi, 1955), 73.

[45] Edwards.

[46] Edwards.

[47] Sherwood, 72-73.

[48] Sherwood, 85-86.

[49] Philip, Schaff, The Seven Ecumenical Councils, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, vol. 14, (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1900), https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf214.html, 316-17.

[50] For a detailed analysis of the edict, see Sherwood, 77-82.

[51] Sherwood, 85-87.

[52] Schaff, 316.

[53] Constas, x-xv.

[54] The Ambigua to John was later attached to be the second half of the later written Ambigua to Thomas. The two works together are known simply as the Ambigua. See section II.

[55] Sherwood, 88-89.

[56] Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration: On Love for the Poor, 14.7, in Maximus, 7.1.

[57] Sherwood, 73.

[58] Maximus, 7.2.

[59] While Maximus does not explicitly list this last one, his response clearly implies that he considers this to be an essential element of the Origenist account.

[60] Maximus, 7.2.

[61] c.f. Maximus, 7.7.

[62] Maximus, 7.3-5, trans. modified.

[63] Maximus, 7.4.

[64] Maximus, 7.5.

[65] Maximus, 7.5.

[66] Maximus, 7.5.

[67] Sherwood, 72.

[68] Maximus, 7.40-43.

[69] c.f. Aristotle, On the Soul, trans. W. S. Hett, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957), 412a4-22.

[70] Maximus, 7.40-42.

[71] c.f. Maximus, 42.9.

[72] Maximus, 41.

[73] While Aristotle also holds that the nature of the soul is to have a body, the Origenists are not only asserting this, but also that it is the nature of the soul to come into body.

[74] While Maximus does not point it out, this Origenist counterargument seems to destroy the fall from the primordial unity of Origenism since it is not a result of nature but sin that bodies come to be in Origenism.

[75] Maximus, 7.42-43.

[76] Constas, 481-83.

[77] Maximus, 7.42-43.

[78] Maximus, 7.42, trans. modified.

[79] ἀποκατάστασις has come to be associated with universalism. I mean it here only as the Origenist doctrine that the beginning and end of history are identical.

[80] Maximus, 7.3.

[81] Maximus, 7.26-27.

[82] Maximus, 7.10; c.f. Rev 21:6.

[83] This is the main thesis of Tollefsen.

[84] Blowers, 230-34.

[85] Maximus, 7.16; c.f. Eph 1:10.

[86] It is generally popular to think of Maximus’s response to Origenism as triadic. Sherwood, 92-127; Balthasar, 137. I have broken it down into four parts instead. Parts two and three are closely connected though and will be considered together in this paper though in section IX, so the triadic nature of the response is still very much at play here.

[87] Balthasar, 127.

[88] Tollefsen, 75-76.

[89] Tollefsen, 27-33; Balthasar, 115.

[90] Tollefsen, 73-76; Maximus himself takes Dionysius, whom he takes to be the real Dionysius the Areopagite, to hold the same view as him. Tollefsen agrees that Dionysius had already Christianized Neoplatonic metaphysics. On the other hand, Balthasar thinks the views of Maximus and Dionysius are opposed. Balthasar, 115-26.

[91] Dionysius, Divine Names, 5.8, quoted in Maximus, 7.24.

[92] Balthasar, 117.

[93] Maximus, 7.15.

[94] c.f. John 1:1-18.

[95] c.f. Maximus, 7.41-42.

[96] “The one Λόγος is many λόγοι and the many are one.” Maximus, 7.20.

[97] “All things are related to him without being confused with him.” Maximus, 7.15; “For by virtue of the fact that all things have their being from God, they participate in God in a manner appropriate and proportionate to each.” Maximus, 7.16.

[98] Maximus, 7.19.

[99] Maximus, 7.19, trans. modified.

[100] Maximus, 7.16, 24,

[101] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1072b14-31.

[102] Maximus, 7.24.

[103] Maximus, 7.6; Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1050a8-9.

[104] “Understand that movement is something that happens to us, and not to the Godhead… The ‘movement’ of the Godhead is the knowledge — through illumination — of its existence and how it subsists, manifest to those who are able to receive it.” Maximus, 1.4.

[105] c.f. Maximus, 7.9; Balthasar, 135.

[106] Balthasar, 135.

[107] Maximus, 7.7.

[108] Maximus, 7.9.

[109] Sherwood, 92-93.

[110] Maximus, 7.10-12.

[111] Maximus, 7.12.

[112] Maximus, 7.9-10.

[113] Maximus, 7.12, trans. modified; Constas translates “ἐνεργείας” here are “energy.” While this translation is not technically wrong, it obscures Maximus’s argument regarding motion and activity. The translation of “divine energy” seems to imply a later Palamite theology of energy which is not present in Maximus, who is only using the term ἐνέργεια in its classical sense, as has been demonstrated. Constas’ own Neopalamite theology influencing his translation is a frequent problem in his translation. For another example of this problem, see Jonathan Grieg, “Intellect, Knowledge, and God in Maximus the Confessor’s Ambiguum 22,” Moses Atticizing, Moses Atticizing, June 20, 2020, https://mosesatticizing.com/blog/maximus-amb22-god-intellect. Constas defends his translation in the introduction, but his defense shows Palamite biases. c.f. Constas, xxvi.

[114] Maximus, 7.12.

[115] Maximus, 2.5, trans. modified.

[116] Maximus, 7.10.

[117] Maximus, 7.12.

[118] Maximus, 7.26.

[119] “Man will remain wholly man in soul and body, owing to his nature, but will become wholly God in soul and body owing to the grace and splendor of the blessed glory of Good, which is wholly appropriate to him.” Maximus, 7.26.

[120] Maximus, 7.16; c.f. Eph 1:10.

[121] Maximus, 7.20.

[122] Maximus, 7.37, 36-39; c.f. Eph 1:23, 4:16.

[123] Blowers 64-66, 96-98.

Bibliography

Aristotle. Eudemian Ethics. Translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1935.

———. Metaphysics. 2 volumes. Translated by Hugh Tredennick. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1933-1935.

———. On the Soul. Translated by W. S. Hett. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957.

Balthasar, Hans Urs von. Cosmic Liturgy: The Universe According to Maximus the Confessor. Translated by Brian E. Daley. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003.

Barnes, Michel René. The Power of God: Δύναμις in Gregory of Nyssa’s Trinitarian Theology. Washington: The Catholic University of America Press, 2001.

Blowers, Paul M. Maximus the Confessor: Jesus Christ and the Transfiguration of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Bradshaw, David. Aristotle East and West: Metaphysics and the Division of Christendom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Cartwright, Sophie. “Soul and Body in Early Christianity: An Old and New Conundrum.” In A History of Mind and Body in Late Antiquity. Edited by Anna Marmodoro and Sophie Cartwright. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2018. 173-190.

Edwards, Mark J. “Origen.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University, revised April 18, 2020. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/origen/.

Feser, Edward. Scholastics Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction. Piscataway: Transaction Books, 2014.

Grieg, Jonathan. “Intellect, Knowledge, and God in Maximus the Confessor’s Ambiguum 22.” Moses Atticizing. Moses Atticizing, June 20, 2020. https://mosesatticizing.com/blog/maximus-amb22-god-intellect.

Maximus the Confessor. On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua. 2 volumes. Edited and translated by Nicholas Constas. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Origen. De Principiis. In Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 4. Translated by Frederick Crombie. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1885. http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0412.htm.

Plato. Sophist. Translated by Harold North Fowler. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1921.

Schaff, Philip. The Seven Ecumenical Councils. In Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series. Vol. 14. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1900. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf214.html.

Sherwood, Polycarp. The Earlier Ambigua of Saint Maximus the Confessor and His Refutation of Origenism. Romae: Pontifium Institutum S. Anselmi, 1955.

Tollefsen, Torstein Theodor. The Christocentric Cosmology of St. Maximus the Confessor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Taylor, A. E. Plato: The Man and His Work. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2012.

Van Riel, Gerd. “Horizontalism or Verticalism? Proclus vs Plotinus on the Procession of Matter.” Phronesis 46, no. 2 (2001): 129-153.